Leo Ryan

| Leo Joseph Ryan, Jr. | |

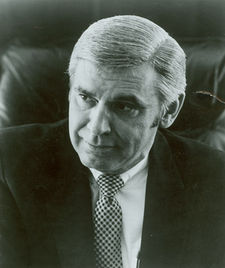

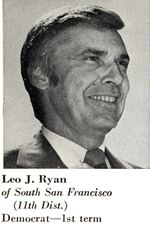

Ryan in 1977–1978 |

|

|

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives for California's 11th congressional district

|

|

| In office January 3, 1973 – November 18, 1978 |

|

| Preceded by | Paul N. McCloskey, Jr. |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | William H. Royer |

| Constituency | 11th District |

|

Member of the California State Assembly for the 27th District

|

|

| In office 1962–1972 |

|

| Preceded by | Glenn E. Coolidge |

| Succeeded by | Lou Papan |

| Constituency | 27th District |

|

Mayor of South San Francisco, California

|

|

| In office 1962–1962 |

|

| Constituency | South San Francisco, California |

|

|

|

| Born | May 5, 1925 Lincoln, Nebraska |

| Died | November 18, 1978 (aged 53) Port Kaituma, Guyana |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Children | Five |

| Occupation | Politician |

Leo Joseph Ryan, Jr. (May 5, 1925 – November 18, 1978) was an American politician of the Democratic Party. He served as a U.S. Representative from the 11th Congressional District of California from 1973 until he was murdered in Guyana by members of the Peoples Temple shortly before the Jonestown Massacre in 1978. After the Watts Riots of 1965, then-Assemblyman Ryan took a job as a substitute school teacher to investigate and document conditions in the area. In 1970, he investigated the conditions of Californian prisons by being held, under a pseudonym, as an inmate in Folsom Prison, while presiding as chairman on the Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform. During his time in Congress, Ryan traveled to Newfoundland to investigate the killing of seals.

Ryan was also famous for vocal criticism of the lack of Congressional oversight of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and authored the Hughes-Ryan Amendment, passed in 1974. He was also an early critic of L. Ron Hubbard and his Scientology movement and of the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon.[1] On November 3, 1977, Ryan read into the United States Congressional Record a testimony by John Gordon Clark about the health hazards connected with destructive cults.[1] Ryan is the only U.S. congressman ever to be killed in the line of duty.[2][3][4][5] He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 1983.

Contents |

Early life and career

Leo Ryan was born in Lincoln, Nebraska.[6] Throughout his early life, his family moved frequently through Illinois, Florida, New York, Wisconsin, and Massachusetts. He graduated from Campion Jesuit High School in Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin in 1943.[7][8] He then received V-12 officer training at Bates College and served with the United States Navy from 1943 to 1946 as a submariner.[9]

Ryan graduated from Nebraska's Creighton University with an B.A. in 1949 and an M.S. in 1951.[6] He taught History at Capuchino High School, and chaperoned the marching band in 1961 to Washington, D.C. to participate in President John F. Kennedy's inaugural parade. Ryan was inspired by Kennedy's call to service in his inaugural address, and decided to run for higher office.[10] He served as a teacher, school administrator and South San Francisco city councilman from 1956 to 1962.[6]

Political career

State of California

In 1962, Ryan was elected mayor of South San Francisco. He served less than a year as mayor, before taking a seat in the California State Assembly's 27th district, winning his assembly race by a margin of 20,000 votes.[10][11] He had previously run for the State Assembly's 25th district in 1958, but lost to Republican Louis Francis.[11] Ryan served as a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1964 and 1968,[6] and he held his Assembly seat through 1972, when he was elected to the United States House of Representatives. He was successively elected three more times to the United States Congress.[6]

U.S. Congresswoman and former California State Senator Jackie Speier described Ryan's style of investigation as "experiential legislating".[10] After the Watts Riots of 1965, Assemblyman Ryan went to the area and took a job as a substitute school teacher to investigate and document conditions in the area. In 1970, using a pseudonym, Ryan had himself arrested, detained, and strip searched to investigate conditions in the California prison system. He stayed as an inmate for ten days in the Folsom Prison, while presiding as chairman on the Assembly committee that oversaw prison reform.[12][13]

As a California Assemblyman, Ryan also served as the Chairman of legislative subcommittee hearings and presided over hearings involving his later successor as Congressman, Tom Lantos.[14] Ryan pushed through important educational policies in California and authored what came to be known as the Ryan Act, which established an independent regulatory commission to monitor educational credentialing in the state.[15]

United States Congress

During his time in Congress, Ryan went to Newfoundland with James Jeffords to investigate the inhumane killing of seals,[16][17] and he was famous for vocal criticism of the lack of Congressional oversight of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), authoring the Hughes-Ryan Amendment,[18][19] which would have required extensive CIA notification of Congress about planned covert operations.[20][21] Congressman Ryan once told Dick Cheney that leaking a state secret was an appropriate way for a member of Congress to block an "ill-conceived operation".[22]

Ryan criticized L. Ron Hubbard's Scientology movement and the Unification Church of Sun Myung Moon. On November 3, 1977, Ryan read into the United States Congressional Record a testimony by John Gordon Clark about the health hazards connected with destructive cults.[1] In this speech before Congress, Congressman Ryan noted that his greatest concern was: "for those young people who have been converted by these religious cults and for their parents, who have suffered the loss of their children."[1] Congressman Ryan went on to note that a parent of one of these young people had first brought Dr. Clark's testimony to his attention.[1] In previous correspondence with this parent, Congressman Ryan thanked the parent for her "detailed letter regarding Scientology", and yet noted that "We haven't yet found a way to attack these jackals who feed on children and young adults who are too emotionally weak to stand by themselves when they reach the age of consent."[23] Congressman Ryan supported Patricia Hearst, and along with Senator S. I. Hayakawa, delivered Hearst's application for a presidential commutation to the Pardon Attorney.[24]

Peoples Temple

In 1978, reports regarding widespread abuse and human rights violations in Jonestown among the Peoples Temple, led by cult leader Jim Jones, began to filter out of the organization's Guyana enclaves. Ryan was friends with the father of former Temple Member Bob Houston, whose mutilated body was found near train tracks on October 5, 1976, three days after a taped telephone conversation with Houston's ex-wife in which leaving the Temple was discussed.[25] Ryan's interest was further aroused by the custody battle between the leader of a "Concerned Relatives" group, Timothy Stoen, and Jones following a Congressional "white paper" written by Stoen detailing the events.[26][27] Ryan was one of 91 Congressmen to write Guyanese Prime Minister Forbes Burnham on Stoen's behalf.[25][26]

After later reading an article in the San Francisco Examiner, Ryan declared his intention to go to Jonestown, an agricultural commune in Guyana where Jim Jones and roughly 1,000 Temple members resided. Ryan's choice was also influenced both by the Concerned Relatives group, which consisted primarily of Californians, as were most Temple members, and by his own characteristic distaste for social injustice.[28] According to the San Francisco Chronicle, while investigating the events, the United States Department of State "repeatedly stonewalled Ryan's attempts to find out what was going on in Jonestown", and told him that "everything was fine".[10] The State Department characterized possible action by the United States government in Guyana against Jonestown as creating a potential "legal controversy", but Ryan at least partially rejected this viewpoint.[29] In a later article in The Chronicle, Ryan was described as having "bucked the local Democratic establishment and the Jimmy Carter administration's State Department" in order to prepare for his own investigation.[13]

Travels to Jonestown

On November 1, 1978, Ryan announced that he would visit Jonestown.[30] He did so as part of a government investigation and received permission and government funds to do so.[31] He made the journey in his role as chairman of a congressional subcommittee with jurisdiction over U.S. citizens living in foreign countries. He asked the other members of his Bay Area congressional delegation to join him on the investigation to Jonestown, but they all declined his invitation.[10] Ryan had also asked his friend Indiana Congressman Dan Quayle to accompany him – Quayle had served with Ryan on the Government Operations Committee – but Quayle was unable to go on the trip.[32]

While the party was initially planned to consist of only a few members of the Congressman's staff and press as part of the congressional delegation, once the media learned of the trip the entourage ballooned to include, among others, Concerned Relatives members. Congressman Ryan traveled to Jonestown with 17 Bay Area relatives of Peoples Temple members, several newspaper reporters and an NBC TV team.[33] When the legal counsel for Jones attempted to impose several restrictive conditions on the visit, Ryan responded that he would be traveling to Jonestown whether Jones permitted it or not. Ryan's stated position was that a "settlement deep in the bush might be reasonably run on authoritarian lines".[33] However, residents of the settlement must be allowed to come and go as they pleased. He further asserted that if the situation had become "a gulag", he would do everything he could to "free the captives".[33]

Jungle ambush

On November 14, according to the Foreign Affairs Committee report,[34] Ryan left Washington and arrived in Georgetown, the capital of Guyana located 150 miles (240 km) away from Jonestown, with his congressional delegation of government officials, media representatives and some members of the "Concerned Relatives".[35]

That night the delegation stayed at a local hotel where, despite confirmed reservations, most of the rooms had been cancelled and reassigned, leaving the delegation sleeping in the lobby.[36] For three days, Ryan continued negotiation with Jones's legal counsel and held perfunctory meetings with embassy personnel and Guyanese officials.[37]

While in Georgetown, Ryan visited the Temple's Georgetown headquarters in the suburb of Lamaha Gardens.[38] Ryan asked to speak to Jones by radio, but Sharon Amos, the highest-ranking Temple member present, told Ryan that he could not because his present visit was unscheduled.[35] On November 17, Ryan's aide Jackie Speier (who became a Congresswoman in April 2008), the United States embassy Deputy Chief of Mission Richard Dwyer, a Guyanese Ministry of Information officer, nine journalists, and four Concerned Relatives representatives of the delegation boarded a small plane for the flight to an airfield at Port Kaituma a few miles outside of Jonestown.[34] At first, only the Temple legal counsel was allowed off the plane, but eventually the entire entourage (including Gordon Lindsay, reporting for NBC) was allowed in. Initially, the welcome at Jonestown was warm,[31] but Temple member Vernon Gosney handed a note to NBC correspondent Don Harris which stated, "Please help me get out of Jonestown," listing himself and Temple member Monica Bagby.[33] That night, the media and the delegation were returned to the airfield for accommodations following Jones's refusal to allow them to stay the night; the rest of the group remained.[34]

The next morning, Ryan, Speier, and Dwyer all continued their interviews, and in the morning met a woman who secretly expressed her wish to leave Jonestown with her family and another family. Around 11:00 A.M. local time, the media and the delegation returned and took part in interviewing Peoples Temple members. Around 3:00 p.m., 14 Temple defectors, and Larry Layton posing as a defector, boarded a truck and were taken to the airstrip, with Ryan wishing to stay another night to assist any others that wished to leave. Shortly thereafter, a failed knife attack on Congressman Ryan occurred while he was arbitrating a family dispute on leaving.[39] Against Ryan's protests, Deputy Chief of Mission Dwyer ordered Ryan to leave, but he promised to return later to address the dispute.[34]

The entire group left Jonestown and arrived at the Kaituma airstrip by 4:45 p.m. local time.[34] Their exit transport planes, a twin-engine Otter and a Cessna, did not arrive until 5:10 p.m.[34] The smaller six-seat Cessna was just taxiing to the end of the runway when one of its occupants, Larry Layton, opened fire on those inside, wounding several.[34] Concurrently, several other Peoples Temples members who had escorted the group out began to open fire on the transport plane, killing Congressman Ryan, three journalists and a defecting Temple member, while wounding nine others, including Speier.[25][40] The gunmen riddled Congressman Ryan's body with bullets before shooting him in the face.[41] The passengers on the Cessna subdued Larry Layton and the surviving people on both planes fled into nearby fields during and after the attack.[34]

That afternoon, before the news became public, the wife of Ryan aide William Holsinger received three threatening phone calls.[42] The caller allegedly stated, "Tell your husband that his meal ticket just had his brains blown out, and he better be careful."[42] The Holsingers then fled to Lake Tahoe and later to a ranch in Houston.[42] They never returned to San Francisco.[42] Following its takeoff, the Cessna radioed in a report of the attack, and the U.S. Ambassador, John R. Burke, went to the residence of Prime Minister Forbes Burnham.[34] It was not until the next morning that the Guyanese army could cut through the jungle and reach the settlement.[34] They discovered 909 of its inhabitants dead; the individuals died in what the United States House of Representatives described as a "mass suicide/murder ritual".[34]

Conviction of Larry Layton

Larry Layton, brother of author and former Peoples Temple member Deborah Layton, was convicted in 1986 of conspiracy in the murder of Leo Ryan.[43] Temple defectors boarding the truck to Port Kaituma warned about Larry Layton that "there's no way he's a defector. He's too close to Jones." [44] Layton was the only former Peoples Temple member to be tried in the United States for criminal acts relating to the murders at Jonestown.[45][46] He was convicted on four different murder-related counts.[47]

On March 3, 1987, Layton was sentenced to concurrent sentences of life in prison for "aiding and abetting the murder of Congressman Leo Ryan", "conspiracy to murder an internationally protected person, Richard Dwyer, Deputy Chief of Mission for the United States in the Republic of Guyana", as well as fifteen years in prison on other related counts.[48] At that time, he would become eligible for parole in five years.[49] On June 3, 1987, Layton's motion to set aside the conviction "on the ground that he was denied the effective assistance of counsel during his second trial" was denied by the United States District Court, of the Northern District of California.[49] After spending eighteen years in prison, Layton was released from custody in April 2002.[50]

Memorial

Burial

Leo Ryan's body was returned to the United States and interred at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, California. The official Congressional Memorial Services for Ryan were compiled into a book: Leo J. Ryan - Memorial Services - Held In The House Of Representatives & Senate Of The U. S., Together With Remarks.[51] Remembering the funeral of her brother held in the San Francisco area, Ryan's younger sister Shannon stated she was surprised both by the number of supporters that attended the funeral, and by the "outgrowth of real, honest sorrow".[3]

For his efforts, Ryan was posthumously awarded a Congressional Gold Medal by the United States Congress and signed by President Ronald Reagan.[52][53][54] He is the first and only member of Congress to have been killed in the line of duty.[2][3][4][5] In President Reagan's remarks upon signing the bill awarding Congressman Ryan the Congressional Gold Medal, he stated: "It was typical of Leo Ryan's concern for his constituents that he would investigate personally the rumors of mistreatment in Jonestown that reportedly affected so many from his district."[52] Ryan's daughters Erin and Patricia had helped to garner support for the Congressional Gold Medal, in time for the fifth anniversary of Ryan's death.[55]

After his death, Ryan's daughter Shannon Jo changed her name to Jasmine and joined Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, a cult,[31][56][57][58] while her sister Patricia became president of the old Cult Awareness Network.[59][60] Ryan's daughter Erin worked for the C.I.A. before eventually becoming an aide to her father's former aide Jackie Speier, who had in 1998 been elected to the California State Senate.[60]

Anniversary

On the 25th anniversary of his death, a special memorial tribute was held in his honor in Foster City, California. Ryan's family and friends, including Jackie Speier and Ryan's daughters, were in attendance. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that "Over and over today, people described a great man who continually exceeded his constituents' expectations."[61] Near the end of the memorial service, parents of those who had died in Jonestown stood to honor and thank Congressman Ryan for giving his own life while trying to save those of their children. After the service ended, mounted police escorted the family and friends into Foster City's Leo J. Ryan Memorial Park. A wreath was laid next to a commemorative rock that honored Ryan.[61] The same year, Ryan's daughter Erin attended a memorial for those who died at Jonestown, at the Oakland, California Evergreen Cemetery.[62] On the anniversary of Congressman Ryan's death, Jackie Speier traditionally visits his grave at the Golden Gate National Cemetery with his daughter and her friend, Patricia Ryan.[33]

For the 30th anniversary, Congresswoman Jackie Speier sponsored a bill to designate the facility of the United States Postal Service located at 210 South Ellsworth Avenue in San Mateo, California, as the "Leo J. Ryan Post Office Building".[63] President George W. Bush signed it into law on October 21, 2008.[64] On November 17, 2008, Jackie Speier spoke at the dedication ceremony at the post office. In part of her speech, she said, "There are those - still, thirty years after his passing - who question his motives, or the wisdom of his actions. But criticism was just fine with Leo. Leo Ryan never did anything because he thought it would make him popular. He was more interested in doing what he knew was right."[65]

Leo J. Ryan Award

The Leo J. Ryan Education Foundation established the Leo J. Ryan Award in honor of the congressman. The Foundation, originally titled "Cult Info", changed its name in honor of the congressman in 1999. It is based in Bridgeport, Connecticut.[66] The first award was given in 1981.[67] Notable recipients include Ronald Enroth, Ph.D.;[68] John Gordon Clark, M.D.;[69] Gabe Cazares;[70] Robert Lifton, M.D.;[70] Louis Jolyon West, M.D.;[70] journalist Richard Behar;[71] Congressman Ryan's daughter Patricia Ryan;[70] Michael Langone, Ph.D.;[72] Flo Conway and Jim Siegelman;[73] and Bob Minton.[67]

Portrayal in film

Congressman Leo Ryan has been portrayed in films about the Jonestown mass murder/suicide, including by actor Gene Barry in the 1979 film Guyana: Crime of the Century,[74] and by Ned Beatty in the 1980 film, Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones.[75] His assassination was also discussed in the 2006 documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple,[76] on The History Channel documentaries: Cults: Dangerous Devotion[77] and Jonestown Paradise Lost,[78] as well as the MSNBC documentary Witness to Jonestown, which aired in November 2008 - the 30th anniversary of Ryan's assassination and the mass suicides at Jonestown.[79]

Electoral history

Source[11]

|

|

Published works

- Books

- USA/From Where We Stand: Readings in Contemporary American Problems, Paperback book, Fearon Publishers, (1970)

- Understanding California Government and Politics, 152 pages, Fearon Publishers, (1966)

- Congressional reports

- NATO, pressures from the southern tier: Report of a study mission to Europe, August 5–27, 1975, pursuant to H. Res. 315, 22 pages, Published by United States Government Print Office, (1975)

- Vietnam and Korea: Human rights and U.S. assistance : a study mission report of the Committee on Foreign Affairs, U.S. House of Representatives, 15 pages, Published by United States Government Print Office, (1975)

- The United States oil shortage and the Arab-Israeli conflict: Report of a study mission to the Middle East from October 22 to November 3, 1973, 76 pages, Published by United States Government Print Office, (1973)

See also

- Leo J. Ryan Federal Building

- Destructive cult

- Seductive Poison

- List of assassinated American politicians

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Clark, M.D., John Gordon; Hon. Leo J. Ryan of California (November 3, 1977). "The Effects of Religious Cults on the Health and Welfare of Their Converts". United States Congress. Congressional Record. http://www.lermanet2.com/house/destructive.htm.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Cuniberti, Betty; Los Angeles Times News Service: Wire services (January 6, 1985). "Daughter of Congressman Killed in Guyana Explains Why She Joined Commune of Controversial Indian Guru". The Record (Bergen Record Corp.): p. A54. "Six years later, 32-year-old Shannon Jo Ryan joined other family members in the White House Oval Office, where President Reagan presented them with Ryan's posthumous Congressional Gold Medal, honoring the only member of Congress ever killed in the line of duty."

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sudol, Karen (November 24, 2004). "Keeping her brother's memory alive : Rep. Ryan's sister won't let people forget him or Jonestown". Asbury Park Press. http://www.rickross.com/reference/jonestown/jonestown32.html. "Ryan is the only member of Congress to have been killed in the line of duty and was posthumously recognized in the 1980s with a congressional award presented by then-President Ronald Reagan."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Internet Archive (2003-11-17). "Congressman Tom Lantos' Remarks on the 25th Anniversary of the Tragedy at Jonestown and the Death of Congressman Leo Ryan". Press release. http://web.archive.org/web/20070627182834/http://lantos.house.gov/HoR/CA12/Newsroom/Press+Releases/2003/11-17-03+Congressman+Tom+Lantos+Remarks+on+the+25th+Anniversary+of+the+Tragedy+at+Jonestown+and+the.htm. Retrieved 2010-01-29. "Among the victims was Congressman Leo Ryan, the first Member of Congress ever killed in the line of duty." (archived page, alternate link)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Epstein, Edward (January 1, 2007). "Lantos the master storyteller, communicator". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/01/01/MNGBDNB8MF1.DTL&type=printable. Retrieved 2008-09-02. "Ryan, the only member of Congress ever killed in the line of duty, was succeeded in a special election by a Republican, but Lantos won a Democratic primary in 1980, beat the GOP incumbent and has never looked back."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 United States Congress. "RYAN, Leo Joseph, (1925 - 1978)". United States Congress. http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000558. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Campion Jesuit High School. "Campion Knights". http://www.campion-knights.org/. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Campion Jesuit High School. "Campion Forever". http://www.campionforever.org/. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Campion Jesuit High School. "Campion Knights Notables". http://www.campion-knights.org/notables.html. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Simon, Mark (December 10, 1998). "A Trip Into The Heart Of Darkness: Always larger than life, Leo Ryan courted danger.". San Francisco Chronicle: pp. A17.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Vassar, Alex; Shane Meyers (2007). "Leo J. Ryan, Democratic". JoinCalifornia.com. http://www.joincalifornia.com/candidate/603. Retrieved 2007-01-25.

- ↑ Wright, Erik Olin (1973). The Politics of Punishment: A Critical Analysis of Prisons in America. Harper & Row. p. 266.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Haddock, Vicki (November 16, 2003). "Jackie Speier – moving on, moving up; Survivor of Jonestown ambush plans run for lieutenant governor.". San Francisco Chronicle: pp. D1.

- ↑ Schwartzman, Edward (1989). Political Campaign Craftsmanship: A Professional's Guide to Campaigning for Public Office. Transaction Publishers. p. 209. ISBN 0-88738-742-X.

- ↑ Gideonse, Hendrik D. (1992). Teacher Education Policy: narratives, stories, and cases. SUNY Press. pp. 49, 50, 65. ISBN 0791410552.

- ↑ Wenzel, George W. (1991). Animal Rights, Human Rights: Ecology, Economy and Ideology in the Canadian Arctic. University of Toronto Press. p. 48. ISBN 0802068901.

- ↑ Hunter, Robert (1979). Warriors of the Rainbow: A Chronicle of the Greenpeace Movement. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. pp. 439, 441. ISBN 0030437415.

- ↑ Olmsted, Kathryn S. (1996). Challenging the Secret Government: The Post-Watergate Investigations of the CIA and FBI. UNC Press. p. 45. ISBN 0807845620.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins University. School of Advanced International Studies (1989). SAIS Review. Original from the University of California. p. 112.

- ↑ Ellis, W. Philip; Barry M. Blechman (1992). The Politics of National Security: Congress and U.S. Defense Policy. Oxford University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0195077059.

- ↑ Knott, Stephen F.. Secret and Sanctioned: covert operations and the American presidency. Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 0195100980.

- ↑ Rozell, Mark J. (1994). Executive Privilege: The Dilemma of Secrecy and Democratic Accountability. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 52. ISBN 0801849004.

- ↑ 1976 Congressman Leo Ryan letter to Ida Camburn, Congressman Leo J. Ryan, December 10, 1976., Congress of the United States, House of Representatives.

- ↑ Hearst, Patricia C.; Alvin Moscow (1980). Every Secret Thing. Doubleday Publishing. pp. 440, 441. ISBN 0385170564.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 299-300, 457

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Hall, John R. (1987). Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0-88738-124-3. page 227

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 458

- ↑ McConnell, Malcolm (1984). Stepping Over: personal encounters with young extremists. Reader's Digest Press. p. 67. ISBN 0883491664.

- ↑ Dawson, Lorne L. (2003). Cults and New Religious Movements: A Reader. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 186, 200, 205. ISBN 1405101814.

- ↑ Rebecca Moore, American as Cherry Pie, 2000, Jonestown Institute, San Diego State University

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Chidester, David (2003). Salvation and Suicide: Jim Jones, the Peoples Temple, and Jonestown. Indiana University Press. xvii, 11, 139, 151, 167, 168, 186. ISBN 0-253-21632-X.

- ↑ Quayle, Dan (1995). Standing Firm: A Vice-Presidential Memoir. Harpercollins. p. 176. ISBN 0061093904.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 Zane, Maitland (November 13, 1998). "Surviving the Heart of Darkness: Twenty years later, Jackie Speier remembers how her companions and rum helped her endure the night of the Jonestown massacre.". San Francisco Chronicle: p. 1.

- ↑ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 United States House of Representatives; Foreign Affairs Committee (May 15, 1979). "Congressional Foreign Affairs Committee report on Ryan's assassination". Report of a Staff Investigative Group to the Committee on Foreign Affairs. United States Congress. http://www.rickross.com/reference/jonestown/jonestown2.html#back.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 481

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 482

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 482-4

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 484

- ↑ Milhorn, H. Thomas (2004). Crime: Computer Viruses to Twin Towers. Universal-Publishers.com. p. 392. ISBN 1581124899.

- ↑ Singer, Ph.D., Margaret Thaler; Janja Lalich (1995). Cults in Our Midst: The Hidden Menace in Our Everyday Lives. Jossey Bass. pp. 28, 237..

- ↑ Snow, Robert L. (2003). Deadly Cults: The Crimes of True Believers. Praeger/Greenwood. pp. 36, 38, 166, 168. ISBN 0275980529.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 Bernstein-Wax, Jessica, "Jonestown still reverberates in Bay Area 30 years later", San Jose Mercury News, November 16, 2008

- ↑ Associated Press (December 2, 1986). "Ex-Cult Member Convicted In Death of Rep. Leo Ryan : '78 Shooting Led to Jonestown Mass Suicide". The Washington Post: pp. A5.

- ↑ Reiterman & Jacobs 1982, p. 520

- ↑ Drew, Bettina (February 1, 1999). "Indiana Jones's Temple of Doom". The Nation. http://www.thenation.com/doc/19990201/drew

- ↑ Associated Press (December 2, 1986). "LAYTON CONVICTED FOR ROLE IN 1978 JONESTOWN KILLING". Boston Globe

- ↑ Staff (December 2, 1986). "LAYTON GUILTY IN GUYANA SHOOTINGS". Sacramento Bee: pp. A1.

- ↑ Bassiouni, M. Cherif (1998). Legal Responses to International Terrorism: U.S. procedural aspects. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. pp. 169, 170. ISBN 0898389313.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 United States of America v. Laurence John LAYTON, 666 F.Supp. 1369, No. CR-80-416 RFP. U.S. (United States District Court, N.D. California. June 3, 1987).

- ↑ Bell, Frank (2003). Larry Layton and Peoples Temple: Twenty-Five Years Later. Department of Religious Studies at San Diego State University: “Alternative Considerations of Jonestown and Peoples Temple”. http://jonestown.sdsu.edu/AboutJonestown/PersonalReflections/bell.htm

- ↑ Joint Committee On Printing; United States Government Printing (1979). Leo J. Ryan - Memorial Services - Held In The House Of Representatives & Senate Of The U. S., Together With Remarks. Washington, D.C.: United States Congress. p. 89.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Ronald Reagan (November 18, 1983). "Statement on Signing the Bill Authorizing a Congressional Gold Medal Honoring the Late Representative Leo J. Ryan". Press release. http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=40789. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Trescott, Jacqueline (November 30, 1984). "Leo Ryan honored (with Medal of Honor)". The Washington Post: pp. v107 pC4 col 5 (10 col in).

- ↑ Staff (November 27, 1984). "Reagan to give medal for slain congressman (Leo J. Ryan)". The New York Times: pp. A25(L) col 2 (4 col in).

- ↑ Herald Staff (July 11, 1983). "PEOPLE UPDATE: PAT AND ERIN RYAN". The Miami Herald: pp. 2A.

- ↑ Endicott, William (January 12, 1981). "Leo Ryan's Daughter Joins Cult : Shannon Jo Ryan Follows Religious Guru". The Washington Post: pp. C1

- ↑ Staff. (December 22, 1982). "Leo Ryan's Daughter Weds Guru Disciple". The Washington Post: pp. D12.

- ↑ Associated Press (November 20, 1984). "Dad 'would understand' why she lives with cult group.". The Chronicle-Telegram, Elyria, Ohio: pp. A6.

- ↑ Tuman, Myron C. (2002). Criticalthinking.Com: A Guide to Deep Thinking in a Shallow Age. Xlibris Corporation. p. 82. ISBN 1401052290.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Dearen, Jason (November 18, 2003). "Erin Ryan wants father to be appreciated". Oakland Tribune. http://www.rickross.com/reference/jonestown/jonestown25.html

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bay City News Report (November 18, 2003). "Tribute to congressman Leo Ryan held in Foster City.". San Francisco Chronicle. http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/gate/archive/2003/11/18/ryan18.DTL. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Delevett, Peter (November 15, 2003). "Two children remember fathers' legacies 25 years after Jonestown.". San Jose Mercury News

- ↑ Govtrack.us. "H.R. 6982: To designate the facility of the United States Postal Service located at 210 South...". http://www.govtrack.us/congress/bill.xpd?bill=h110-6982. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ The White House. "President Bush Signs H.R. 3511, H.R. 4010, H.R. 4131, H.R. 6558, H.R. 6681, H.R. 6834, H.R. 6847, H.R. 6902, and H.R. 6982 Into Law". http://georgewbush-whitehouse.archives.gov/news/releases/2008/10/20081021-7.html. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Congresswoman Jackie Speier. "Leo J. Ryan Post Office Dedication". http://www.house.gov/htbin/blog_inc?BLOG,ca12_speier,blog,999,All,Item%20not%20found,ID=081117_2533,TEMPLATE=postingdetail.shtml. Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Clarkson, Frederick (October 9, 2000). "Million Moon March". Salon (www.salon.com). http://www.salon.com/news/feature/2000/10/09/march/print.html. Retrieved 2010-04-12.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 2001 Leo J. Ryan Education Foundation Conference, October 26–28, 2001, theme: "Cults and Terrorism: Abuse of the Vulnerable."

- ↑ Bio Sheet, Ronald M. Enroth, June 1, 1996.

- ↑ The Boston Globe, "Psychiatrist was authority on danger of cults, Dr. John Clark, 73", Globe Staff, October 10, 1999, Tom Long.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 70.3 Voir détails et lauréats du Prix Ryan, French site listing Leo J. Ryan award recipients

- ↑ Leo J. Ryan award winner Richard Behar, 1992 speech

- ↑ ICSA Annual International Conference, Conference Handbook, ICSA Annual International Conference, Denver, Colorado, June 22–24, 2006.

- ↑ Profile, publisher, Flo Conway & Jim Siegelman, Stillpoint Press, Authors of Snapping, Holy Terror, and the new Dark Hero of the Information Age

- ↑ René Cardona Jr.. (1979). Guyana: Crime of the Century. [Film]. Universal Pictures.

- ↑ William A. Graham. (1980). Guyana Tragedy: The Story of Jim Jones. [Film]. CBS Television.

- ↑ Stanley Nelson. (October 20, 2006). Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple. [Documentary]. Firelight Media.

- ↑ The History Channel. (2006). Decoding the Past: Cults: Dangerous Devotion: Scholars and survivors discuss the mystery of cults.. [Documentary]. A&E Television Networks.

- ↑ The History Channel. (2006). Jonestown Paradise Lost: Congressman Leo Ryan's fatal journey into "Jonestown," a community carved out of the jungles of Guyana by followers of pastor Jim Jones.. [Documentary]. A&E Television Networks.

- ↑ MSNBC. (2008). Witness to Jonestown. [Documentary]. NBC.

References

- Ryan, Leo J. (1966). Understanding California Government and Politics. Palo Alto, CA: Fearon Publishers

- Hall, John R. (1987). Gone from the Promised Land: Jonestown in American Cultural History. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 0887381243

- Reiterman, Tim; Jacobs, John (1982). Raven: The Untold Story of Rev. Jim Jones and His People. Dutton. ISBN 0525241361

Further reading

- Biography, Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Report to the committee on Foreign Affairs, May 1979 Congressional Foreign Affairs Committee report on Ryan's assassination, May 15, 1979

- Congressional Gold Medal, Text of the act issuing the Congressional Gold Medal and an FBI report summary as well as an article on both Jones and his involvement and the investigation

- The Leo J. Ryan Award, Presentation, 2001, awarded to Bob Minton, introduced by Priscilla Coates

- On the 25th anniversary of the Jonestown Massacre and Ryan's assassination, 2003, Press release from Rep. Tom Lantos, California 12th Congressional District

External links

- JoinCalifornia, Election History for the State of California

- Leo Ryan at Find a Grave

- Congressman Leo J Ryan Memorial Page, hosted by Arnaldo Lerma

- Leo J Ryan Memorial park in Foster City, California

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Unknown |

Councilman, South San Francisco, California 1956–1962 |

Succeeded by Unknown |

| Preceded by Unknown |

Mayor of South San Francisco, California 1962 |

Succeeded by Unknown |

| California Assembly | ||

| Preceded by Glenn E. Coolidge |

Member of the California State Assembly 1962–1972 |

Succeeded by Lou Papan |

| United States House of Representatives | ||

| Preceded by Paul N. McCloskey, Jr. |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 11th congressional district 1973–1978 |

Succeeded by William H. Royer |

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||